A Little Catechism from the Demon

What is a demon? Study my life.

What is a mountain? Set out now.

What is fire? It is for ever.

What is my life? A fall, a call.

What is the deep? Set out now.

What is thunder? Your power dry.

What is the film? It rolls, it tells.

What is the film? Under the Falls.

Where is the theatre? Under the hill.

Where is the demon? Walking the hills.

Where is the victory? On the high tops.

Where is the fire? Far in the deep.

Where is the deep? Study the demon.

Where is the mountain? Set out now.

Study my life and set out now.

EDWIN MORGAN

****

From the first line of this intriguing, unsettling “catechism”, we can reasonably infer that the demon is the speaker, uttering both the questions and the pedagogically correct responses. So the first question for us is the one that begins the poem (“What is a demon?”) and is dodged. We have only a series of selective questions and oblique responses from which to build a picture. At least we know it’s a teacher demon: it wants to be understood, to spread demonic knowledge and be an exemplar for the student demons.

The voice sounds robotic: perhaps this is a post-human AI demon, programmed for re-mastery of a near-devastated planet. Non sequiturs sometimes suggest it’s still in the process of mastering the English language. It’s certainly not big on clear explanation. But perhaps this make it all the more attractive to the students it’s addressing.

Much of the imagery is drawn from the natural world, and the symbolism of these images is clear. The demon seems to favour mountains, hill-tops and “the deep”: it’s possibly a fire-worshipper. There is a question as to whether there’s a gap between its ambition and its actual power. The response in the sixth line (“What is thunder? Your power dry”) is elusive: has the power become dangerously less by being “dry” – or more potent?

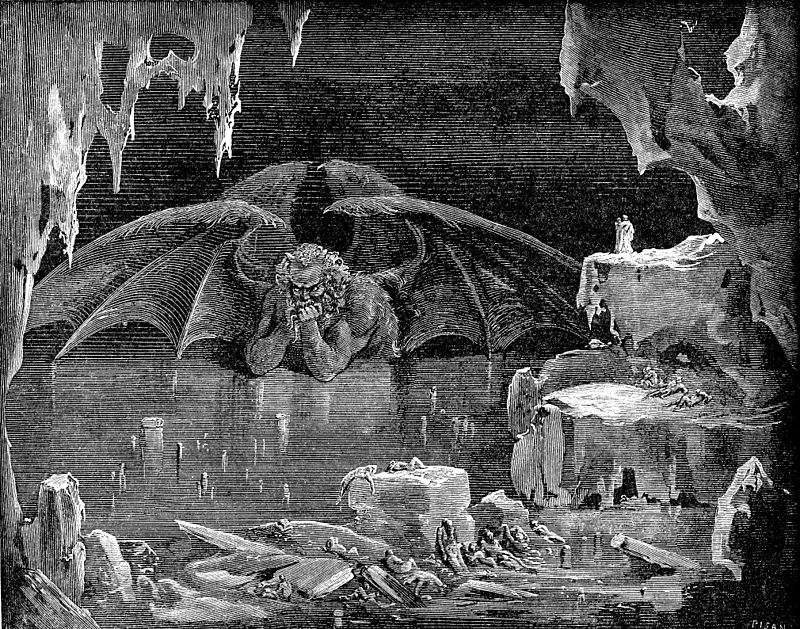

The demon might itself be identified with Satan (see line four). It could equally be a benign daemon, or simply a neutral force of nature. It’s fascinated, though, by two non-demonic human inventions – theatre and film. These media have perhaps seduced it to a further desire for “victory” and the means for achieving it. Film, after all, has the power to tell its story.

The 15-line catechism is in two sonnet-like parts, the first eight questions beginning with “What” and the following six with “Where?” This suggests a movement outwards from theory to the experience of the phenomena invoked. If the demon has a message, it’s that knowledge is achieved by action: studying the life, and then setting out now.

Questions breed questions and the skilful avoidance of direct answers increases the thrill of interest. Edwin Morgan’s experimental and science fiction poems often imply joyful adventure, boundless optimism. This set of coolly mysterious imperatives leaves us wondering about the nature of the quest, so urgently and indeterminately presented. That repeated call to “set out” somehow implies that human history, even after catastrophe, will start up and continue as before, meeting the challenges of its newly elemental setting. We’ll still want mastery. We’ll still rush to “set out now”. And perhaps Edwin Morgan, in his wisdom, is saying that this is the only right thing to do. The demonic is the human.

A Little Catechism from the Demon is published in Centenary Selected Poems by Edwin Morgan.