Lines from Hesiod’s Theogony translated by Thomas Cooke

Shepherds, attend, your happiness who place

In gluttony alone, the swain’s disgrace;

Strict to your duty in the field you keep,

There vigilant by night to watch your sheep:

Attend, ye swains, on whom the Muses call,

Regard the honour not bestow’d on all;

’Tis ours to speak the truth in language plain

Or give the face of truth to what we feign.”

So spoke the maids of Jove, the sacred Nine,

And pluck’d a sceptre from the tree divine;

To me the branch they gave, with look serene

The laurel ensign, never fading green:

I took the gift, with holy raptures fired.

My words flow sweeter, and my soul’s inspired;

Before my eyes appears the various scene

Of all that is to come, and what has been.

Me have the Muses chose, their bard to grace,

To celebrate the bless’d immortal race;

To them the honours of my verse belong!

To them I first and last devote the song:

But where, O where, enchanted do I rove.

Or o’er the rocks, or through the vocal grove!

Now with th’ harmonious Nine begin, whose voice

Makes their great sire, Olympian Jove, rejoice;

The present, future, and the past, they sing,

Join’d in sweet concert to delight their king;

Melodious and untired their voices flow;

Olympus echoes, ever crown’d with snow.

The heavn’ly songsters fill th’etherial round;

Jove’s palace laughs, and all the courts resound

Soft warbling endless with their voice divine,

They celebrate the whole immortal line.

HESIOD

****

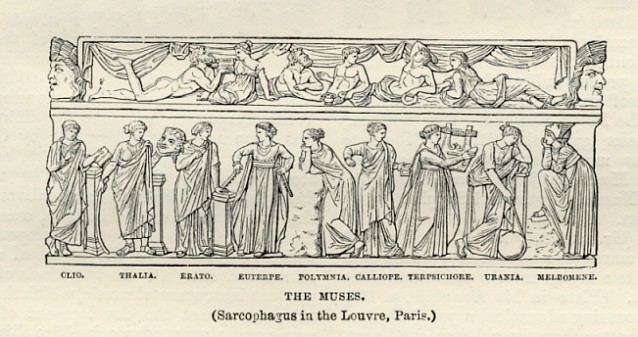

The epic poet, Hesiod, lived in Boeotia around 700 BCE, a contemporary of Homer. We know more about Hesiod, because of the (unreliable) biographical details his poetry records. His father came from Kyme, a major coastal city in Aeolis, now Turkey. Hesiod lived and farmed at the foot of Mount Helicon, and one day encountered its nine residents, the Muses. So began his “singing of the race of Gods”.

I became interested in the Theogony through a short quotation in Penelope Murray’s modern translation: “We [the Muses] know how to tell many lies which are like the truth, but we also know how to tell the truth if we wish.” It intrigues me to transport that evaluation to contemporary writing in English, and our own literary and documentary genres.

Could the distinction between truth and seeming-truth be relevant not only to the classical epic, but to lyric poetry now? Hesiod had no doubt that truth-telling was superior to lying. But, as Murray asks, are lies (pseudea) falsehoods or just stories, ie fiction?

That personal encounter with the Muses and the narrative it inspires is no doubt truth for Hesiod. It’s his allegorical interpretation of the wonderful moments when ideas flow, images brighten and a voice not the writer’s own seems to be speaking. Inspiration: an unfashionable concept, but still a psychological reality.

Hesiod receives important gifts from his inspirers: the laurel sceptre and the poetic voice. He acquires both bardic and kingly status. These are not really separate honours, as Thomas Cooke’s translation (lines 12-14) makes clear: the poetic voice itself has been granted highest authority. Hesiod does not of course rival Super-King Zeus (“Olympian Jove”), but he has the right to settle disputes, deliver judgments and write those handbooks on agriculture, social behaviour and economics which are really “metaphor for didacticism about man”. He is the supreme narrator of the truth.

Hesiod is sometimes described as the first poet to have a conscious sense of himself as an individual writer. But it also seems plausible that “Hesiod” is a persona. The name Hesiodos means: “He who sends forth the voice.” That naughty brother, Perses, the target of some of Hesiod’s sage advice in Works and Days, could also be a useful fiction.

Whether or not “Hesiod” is a mask, there’s no doubt about the existence of his 18th-century translator, Cooke (1703-1756) – sometimes nicknamed “Hesiod” Cooke. He was the son of an Essex innkeeper, and rose to rival Alexander Pope as classical translator. Pope gave him a brief jab in The Dunciad, in retaliation for Cooke’s satire The Battle of the Poets, in which Pope and the Tories are trounced. Neither poet seems to have taken Hesiod’s advice, that revenge should be avoided as it hurts the vengeful. And who indeed would want a politically corrected Pope, a ponderous parson of a pontiff without the white-hot sneers? There’s more than one way, after all, to be didactic.

I quoted the prose translation above that sent me to Hesiod. This is what Cooke does with the same speech: “’Tis ours to speak the truth in language plain / Or give the face of truth to what we feign.” It rolls smoothly enough but, despite repeating “truth”, it lacks the beautifully angled emphasis. There are certainly some strong descriptive passages in Cooke’s Theogony, not least when he writes about the great Zeus’s thunderstorms. As poetry, Cooke’s couplets are often masterly in their compression, and sometimes energetic, but I think they illustrate why the 18th-century translator’s prosodic choice, the heroic couplet, seems to readers now – and even to some critics then – too tight and trite.

Cooke’s translation was the standard one for years, and it has been significant for later poets. There’s an interesting argument here, for example, for the influence of the Theogony on William Blake.

No poets today would claim Hesiod’s kingly/queenly authority. But many of the best have chosen to “sing” important truths to power. And Hesiod’s reminder that Mnemosyne, the Titan mother of the Muses, conceived her nine daughters by no less a father than Zeus, still resounds as a great metaphor. Memory plus electricity – what else is inspiration?